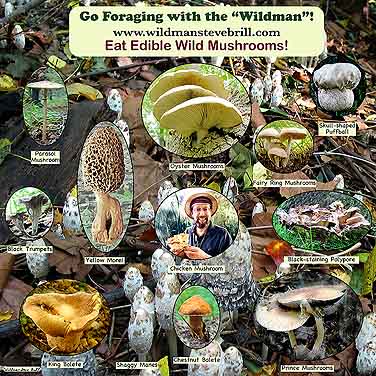

The Amanitas (Amanita species)

Hey, Mom... let's put this in the stew we're making for Aunt Tillie...she'll flip!

Amanita Overview

General Information These strikingly beautiful gilled mushrooms include some of the deadliest species in the world. (They remind me of some of the women I've dated.) Because they account for 90% of mushroom fatalities, this is a very important family to learn (also, you never know when the boss may drop over for dinner).

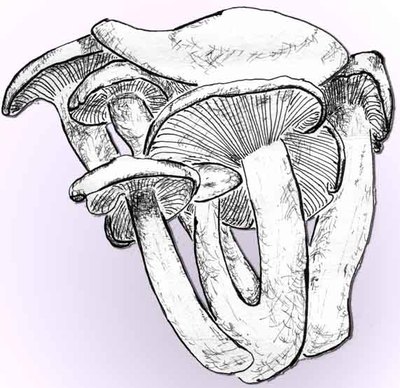

Although it's not always easy to tell species apart, the amanita group itself is not hard to learn or to avoid. Not every amanita species has all the characteristics described below, but all amanitas have enough of them that even a young child can learn to point out amanitas:

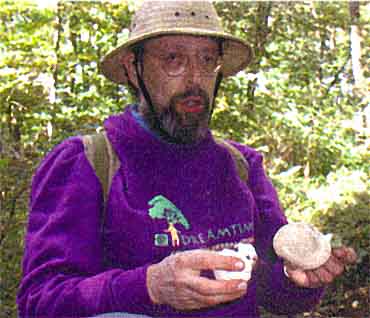

A family that had attended a tour where we found lots of amanitas was watching a TV mystery six months later. When the murder victim was killed by mushroom poisoning, the family's 6-year-old son chanted: "It must have been an amanita!"

Habitat With very few exceptions, amanitas grow on the ground near trees, with which they exchange nutrients. Unless they're interacting with evergreens, you usually see them in the summer, when trees are active.

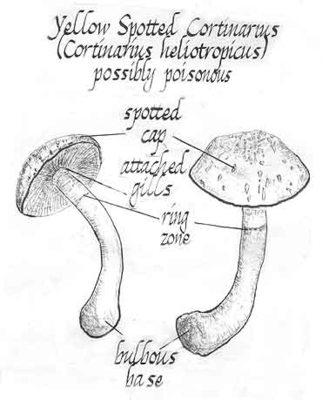

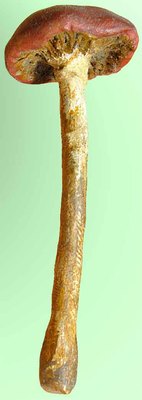

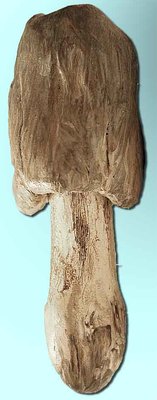

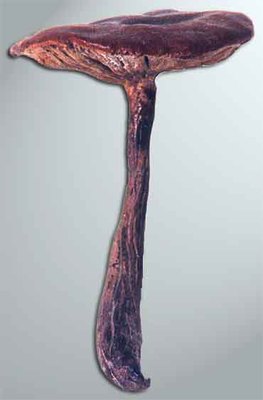

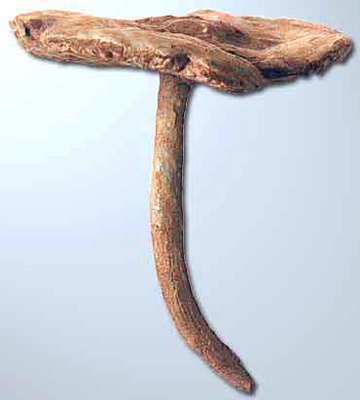

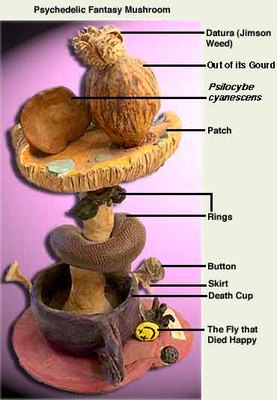

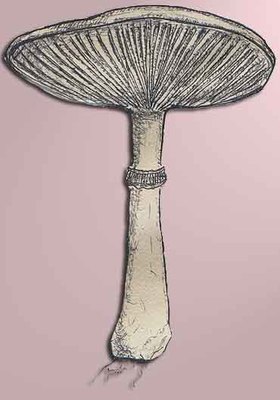

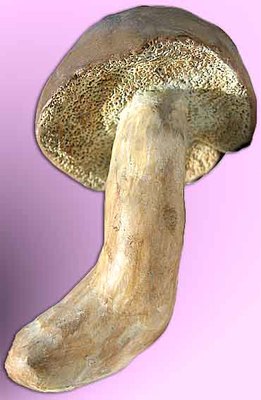

Universal Veil When very young, amanitas are enclosed in a membrane called a universal veil. When the mushroom bursts out, remnants of the universal veil may form an underground sac surrounding the stem's often bulbous base (easy to miss if you carelessly break off the mushroom at ground level), affectionately known as the cup of death.

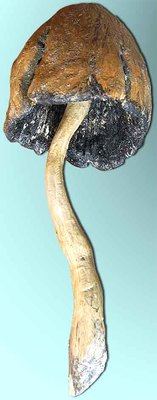

Or the universal veil may break into patches of tissue that can adhere to the cap, or sometimes to the stem, unless rain washes the patches away.

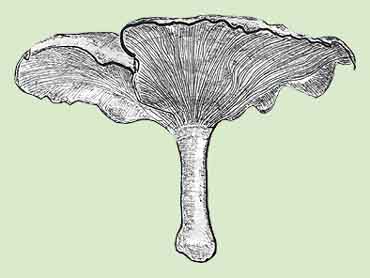

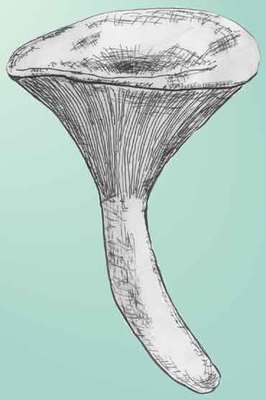

Partial Veil Amanitas usually have a partial veil that covers the gills before the mushroom is mature enough to make spores. When the cap opens like an umbrella, this delicate partial veil often adheres to the stem, forming a ring or skirt. But not all amanitas have this partial veil.

Gills Amanitas generally have white gills, and the gills are almost always free—there's a small space separating the them from the stem, so you can break off the stem from the cap without tearing the gills.

Spores Amanitas' microscopic spores and their spore prints are white. Stem The stem may end in a bulbous base, sometimes covered by a sac-like membrane. Sometimes there may be ridges near the stem's base, or patches of tissue on the stem.

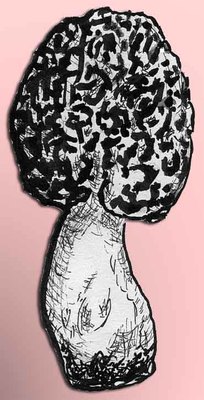

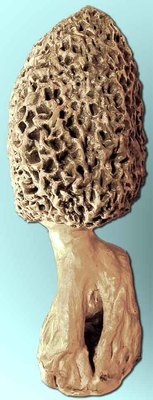

Look-Alikes Confusing amanitas with other mushrooms is the main cause of mushroom poisoning deaths.

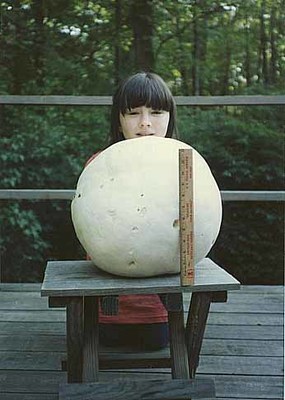

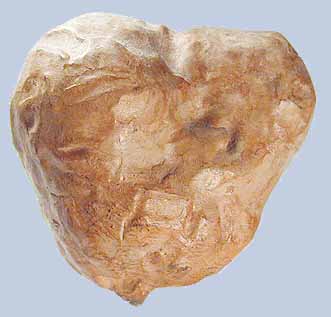

Very young amanitas, called buttons, resemble puffballs, but when you cut puffballs open, they're undifferentiated inside. An amanita button has a cap, stem, and gills inside.

Amanitas share many characteristics with lepiotas (a group with edible and poisonous species). But you can detach a lepiota's ring and run it up and down the stem like a napkin ring. If you try this with an amanita's ring, it breaks apart. Once you've learned these two groups, you'll also notice that the lepiotas are longer and more slender, while the amanitas are shorter and more squat.

Young field mushrooms (Agaricus species), many of which are edible, also resemble amanitas because field mushrooms may have white, free gills when very young (the gills turn brown), sometimes after a pink stage, when the field mushroom matures, but amanita's spores are always white. Field mushrooms' spore prints are brown, while amanitas' are white.

Toxicity Not all amanitas are poisonous, but the edible and deadly species can look so much alike, and there are so many other safer groups, that people should never eat amanitas.

On the positive side, even the most toxic amanitas reportedly taste great, and you don't have to worry about symptoms until 8-12 hours after eating them. Of course, by then it's too late to pump your stomach! And you can eat the most poisonous amanitas with impunity if you happen to be an eastern box turtle. And if a human then eats you, you get revenge—the human dies of amanita poisoning.

The worst of the amanita toxins prevent your cells from making new proteins, and this kills them. Cells in the digestive tract, with the fastest metabolism, go first, leading to days of abominable abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea.

After a few days of this, new cells replace the dead ones, and the symptoms abate. But the toxins recirculate in the bloodstream. The same fate befalls the cells of the liver and kidneys, and death soon ensues.

Doctors shunt the blood through filters to remove the toxins. They use dialysis to replace the kidneys, and give the patient a liver transplant. Sometimes the patient can be saved.

Alternative practitioners recommend psilymarin, a concentrated extract of the milk thistle, which stimulates cells to produce new proteins. This only helps cells that aren't already dead.

The best way to deal with amanita poisoning is never to eat an amanita!