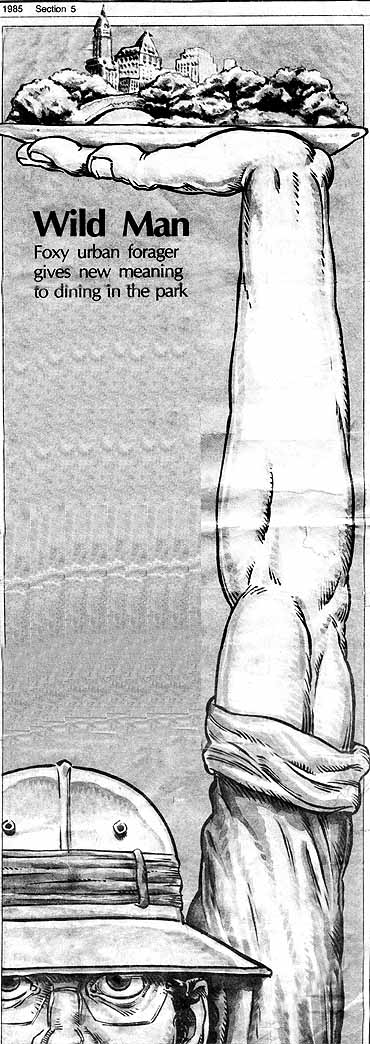

Wild Man

Chicago Tribune

September 23, 1985 By Kenneth Clark

New York—Steven Brill bills himself as "the Wild Man" but doesn't look like one. Perched on his 10-speed bicycle, eyes shielded by a pith helmet and backpack loaded with gardening tools, field guides and botanical drawings, he more closely resembles the scholarly sort—bearded, bespectacled, articulate and quirky. But one habit sets him apart: Steven Brill eats weeds.

Not only does he eat weeds, but to the everlasting consternation of New York Parks Commissioner Henry Stern, whose city park rangers hunt him as if he were a fox with designs on the henhouse, Brill is busy teaching other New Yorkers to eat weeds as well. He walks his students through the city's parks, where they collect mushrooms, nuts, berries and myriad edible greens and considers his work a public service.

“His activities are completely illegal,” Stern said. “He picks flowers and shrubs and he serves them to his clients. The parks are to enjoy, not to destroy.” “Its fun to forage,” Brill said. “Grown-ups like it. Senior citizens like it, little children just go crazy. I can prove that in the five years I’ve been doing this, every single plant stand I’ve ever approached is still there and flourishing. I’m not backing down. If we leave our parks in the hands of the politicians, they'll continue doing what they're doing and destroy everything.”

In Brill’s view, what the politicians are doing, locally nationally, is exploiting the environment for development and recreation that consists of nothing more than walking from Point A to Point B, then sitting down and having a beer and a cigarette."

Brill, who calls Stern “a former city councilman with no training whatsoever in botany or the ecology,” especially objects to the Park Department’s determination to keep its open areas, from Central Park to the seashores of Brooklyn, pruned like lawns rather than allowing nature to take its course. Such pruning, Brill said, eventually will leave New York's green and wooded stretches eroded, sterile and devoid of diversity.

“In the beginning, I got along well with the Parks Department,” he said. “Commissioner Gordon Davis told me I should be discreet but go ahead. He wasn't going to break my bun for collecting

dandelions. But he left office and Henry Stern came in, and he has the park rangers looking for me under the pretext that we are destroying the parks. My work doesn't harm the ecology. It brings people into the ecology. To protect the ecology is not having bureaucrats and politicians coming in with bulldozers."

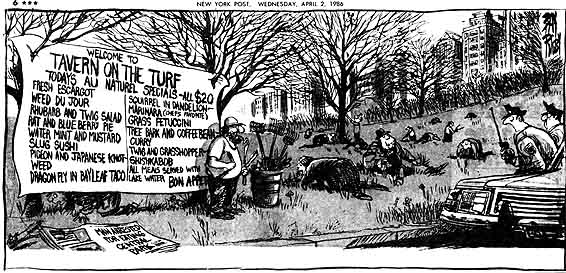

Steven Brill [left], who calls himself "the Wild Man," teaches New Yorkers how to live off the land, a practice New York City park rangers find extremely unpalatable.

Many who follow Brill, and he said there have been thousands in the last five years, grew up in New York's concrete canyons thinking vegetables grow in cans. They are fascinated at the prospect of dining from what most of the world considers a weed patch fit only for hoe and herbicide. A recent foray with Brill that ranged from Forest Park in Queens to the shores of Jamaica Bay, with a dozen students in tow, netted a banquet of horse mushrooms, puffballs, amaranth (better known as pigweed), lamb’s-quarters, Asiatic day flower, wood sorrel, sweet wild plums, and a bushel of butternuts. Stern, however, was not impressed when told that the day's take, drawn at Brill's insistence from only a fraction of each patch, with nothing uprooted, was delicious.

“Well, you just ate our park land,” he said with a trace of bitterness. “Bon appetit. Why don't you eat in restaurants?”

Why indeed? With an estimated 14,000 restaurants in Manhattan alone and with a produce stand on practically every street corner, why would anyone want to forage?

“You go to the supermarket and buy raspberries and you know the ones in the bottom of the carton are going to be moldy and rotten and the others will be big and beautiful looking but have almost no flavor,” Brill said. “They're grown on depleted soil and sprayed with insecticides, and the only reason they grow at all is because of all the artificial fertilizers that are used. Pick raspberries in the park and you're getting exercise, sunshine, contact with nature and much better-tasting fruit, and by picking the berries, you're stimulating the bush to grow. It's very bad for the bush to have the fruit just sitting there rotting on the branch. Mushrooms you buy in the store are grown on manure and sprayed with more chemicals to kill flies than all the other vegetables in the supermarket, and they taste like it.”

Brill's chief concern, however, is the one group he said he finds hardest to educate. They're the poor and the hungry who could improve their diets with the sort of knowledge he passes out on his foraging expeditions. Brill charges $15 a head for his trips, but poor people, when he can get them interested, go along at no charge.

Because Mother Nature's pantry contains the toxic as well as the tasty, a foray with Brill takes on a genuine flavor of adventure, leaving the novice forager with that superior feeling that always comes with finding out something most people don't know.

Brill, 36 and a confirmed vegetarian, did not start out to become a naturalist playing Peter Rabbit to Stern's Farmer MacGregor for a living. He entered George Washington University as a premed student but switched to psychology halfway through and wound up taking every botany course he could fit into his schedule. It was, he said, memories of summer camp when he was a child growing up in Queens that eventually led him to his true vocation.

“My mother taught me berries when I was a child,” he said. “Subsequently, when I went to summer camp, the food was atrocious and I found the wild berry knowledge very useful in giving me a supplement to the horrible summer camp food. Then, when I was an adult, I saw Greek ladies picking things in Cunningham Park. Remembering the berries I'd picked as a child, I stopped my bike and went into the park, and even though they could hardly speak English they were able to tell me they were picking grape leaves. I made a stuffed grape leaf recipe with brown rice, tofu, ginger, garlic and raisins and it was out of this world. That was the turning point. I became very interested in wild foods and started pursuing them.”

Brill's apartment is nothing if not organic. It is a clutter of drying racks, ovens, pulp extractors and packets of clay from which its owner sculpts mushrooms of every species.

“Half my food comes from the wild,” Brill said. “It takes years to learn this on your own and there are only a handful of people in the whole country who have this kind of knowledge. It's just about only me for this area. It's not easy making a living at this, but it's getting better and better every year. People are becoming more ecologically aware. I get by between writing articles, selling sculptures and giving lectures and nutritional and herbal consultations.”

He also gets by by keeping a sharp lookout for Stern's rangers and leading his clients deep into forested parks where the arm of the law seldom ventures. Being caught is costly. “Whenever we catch him, we fine him and he pays the fine, yet he conducts these forays repeatedly,” said Stern.

[Wildman's note: This was a bald-faced lie. Stern's minions were never able to catch me in mid-bite, and I was never fined, which is why he mounted his disasterous sting operation the following year.]

“We oppose Steven Brill as we would oppose any predator or poacher.”

“Tell people my address and phone number," said Brill. “There are bountiful things to eat growing in every major metropolitan area in the nation and I want to share my knowledge with everyone.”